15. Devil: He’s in the details (or is he?)

Flash forward a few years to me in college, and I had an axe to grind.

An axe I would gladly take to the philosophical trees that bore bad fruit and throw them into the fire.

I was a dude with some MAJOR HANG UPS. I wanted to live my life as freely as I could, but I also had this ancient conservative Christian belief system I dragged around with me, and its shadow loomed over everything I did.

The summer of that year, Johnny Cash recorded a song with U2, that had a lyric in it I thought only someone with a certain very specific kind of religious background would sing:

I went out there

In search of experience

To taste and to touch

And to feel as much as a man can

Before he repents

That was me, wanting to do it all, and with hopes and fears shaped by years of dogma I felt I had not truly tested to make sure it was true.

The hero’s journey

I was ostensibly in college to study theater and creative writing, but in the background, I was taking as close to a stealth program in theology as I could take at a radically progressive school with no religious affiliation.

I was either going to blow up Christianity as a fraud, or finally prove there was something to it. I was desperate to know the truth.

It was out of this desperation that I tore through all these books by Joseph Campbell (who had taught at my college when he was alive), and through many ancient myths, such as the Iliad and the Bacchae of Euripides and other authors of classic literature, hoping to nail down the idea that all these religions were essentially the same.

The modern world can easily see the ancients as trying to give names and causes to the irrational and unexplainable by attributing them to Gods. If Achilles did extraordinarily well on the battlefield, it was because the gods had his back. If he refused to go out to the battlefield because he was in a petulant funk, even though his sense of honor required Achilles to fight for his city, it must have been the gods who clouded his judgment, much like the way that God hardened Pharoah’s heart in Exodus, so that he would not release the Israelites from slavery until more plagues had passed. How else could the irrational be explained?

Joseph Campbell had the idea that all religions in the world followed a certain mythical pattern. “The Hero’s Journey,” as it was called, could be seen in mythical stories from Beowulf to the Gospels to Star Wars: the hero leaves his home, faces challenges, learns divine mysteries, and comes back to share his wisdom with his people.

I was exploring the idea that Christianity was just one of a long chain of mythical stories we humans used to explain our confusing and complex existence here on earth. I posited that the early myths were just pure just-so stories, ways that parents explained the confusing universe to their kids—such as why snakes crawl instead of walk. Then, later, interpreters re-structured those stories into codified systems that helped people understand right from wrong and to behave in a societally accepted way.

If Christianity turned out to be just a made-up legend, like Zeus and Hercules, with the ultimate goals of explaining the weird and controlling the masses, then I had no responsibility to follow the Gospels as though they were “gospel truth.”

I would be free to conduct myself as I pleased.

Speak of the Devil (and he will appear?)

As part of this multi-pronged attack on the religion of my youth, I also went after the integrity of Christian teaching itself. I was convinced that the Christianity I had inherited was not really what the Bible itself said.

This was why I ended up in the middle of the night, cranked up on an endless stream of coffee and cigarettes, sitting with my grandfather’s Thompson Chain Reference Bible in the college coffee house, tearing eagerly through the text in search of the Devil.

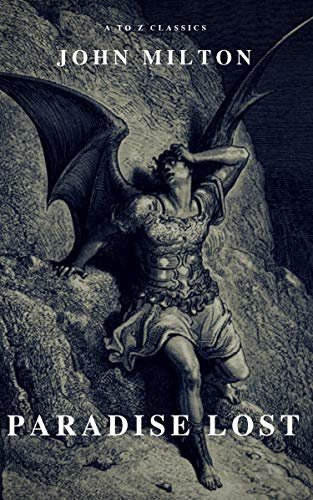

I was in a literature class where we were studying Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Inferno. As I read the detailed descriptions with which these classic poets painted a picture of the pre-creation politics of God, Satan, and the fall of the angels, as well as the lurid images of the descending levels of punishment in Hell, I wondered—where did they get all their information? Was it in the Bible, or were they just making it up

After all, so much of our received imagery of Satan and Hell were from these early pop culture portrayals, which had continued replicating themselves all the way down through the ages to our modern movies and TV shows.

But if they were not what the Bible really said, but just the creations of feverish medieval imaginations trying to scare parishioners into good behavior and regular tithing, then did I really have any responsibility to believe or fear these images?

I remember a conversation early in the semester with my professor, who was a professing Christian, albeit from a much more progressive corner of the Church than I had come from.

We were discussing Dante, and I had an idea that Dante’s Paradise—his later description of Heaven—should be just the opposite of his Inferno. I proposed that it should have been a mountain with distinct levels, as Dante had constructed, but that every level should allow the believer to indulge in whatever sins they had avoided on Earth so that they could get to Heaven.

My professor was amazed.

“I’ve always heard about forms of Christianity that spend much of their energy avoiding sin to avoid going to Hell, but I’ve never met and talked with someone from those traditions,” he said. “I have to tell you, there is more to Christianity than avoiding going to Hell.”

I left his office that day wondering what this other Christianity he was describing looked like. Not like white robes and an eternity playing hymns on harps on clouds in Heaven, I hoped.

I would have to take on Heaven and Hell next, and see what the Bible really said about those two ultimate destinations. In the meantime, I was facing down the Prince of Power of the Air himself, Satan.

Where the devil (is the Devil)?

The narrative that I read in Milton was the same one I had grown up with, in which a bright and favored angel Lucifer rebelled against God, and along with his followers were banished from Heaven. I had been taught that God prepared Hell for the figure now called Satan and his demons (the angels who had followed him), and that Satan was now committed to taking down as many humans with him as he could.

But what I came up with from the Bible shocked me. More than that, it was what I didn’t come up with in the Bible.

The story that Milton told was barely there at all. There were various characters—the serpent in the Garden of Eden, Satan (otherwise known as the adversary), Lucifer (the son of the morning who fell from heaven), Beelzebub, the Beast of the book of Revelation, and other various destroyers and deceivers.

But it is not clear that these are all the same character.

Nowhere is it clearly stated that the serpent is Satan (in fact, the just-so story part of the Eden narrative suggests that he might just be a snake, and this might be the explanation for why snakes crawl), nor is there a direct throughline that demonstrates that Lucifer is Satan.

It’s not even totally clear what the relationship is between God and Satan. While the last book of the Bible, Revelation, shows Jesus locking a Satan-like figure, Abaddon, in a pit of fire, the book of Job shows God and Satan casually hanging out, if not exactly as friends, then at least as something like co-workers.

What this research showed me was that I didn’t know the Bible anywhere nearly as well as I thought I did. Here was a major tenet of the faith that I held on to so tightly, and it wasn’t in the Bible. Scraps of it were there, but it could only be woven together into a full narrative with a lot of imagination and help from outside the Bible.

And now, as I had anticipated—maybe even feared—everything I thought I knew from the Bible was suspect. I couldn’t believe anything I heard across the pulpit, because it all might be just another myth woven together from someone trying to make sense of it all.

What if the whole Bible was a mismatched set of different myths created by different people, tied together by little more than a thread of tradition, but with no solid through line of its own, other than the one we put there ourselves?

Far from feeling freed by this revelation, I felt dread. I was uneasy—a little untethered from the world around me.

I needed to study the entire Bible—MYSELF—if I was going to know what it really said. Then I could judge for myself what was true, what was not, and where to go from here.

My hope—and my fear—was that it would end up not saying anything at all.